The Government’s recent decision to shut down 33 State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) is commendable and a step in the right direction. Sri Lanka has far too many SOEs, with the State entangled in almost every sector imaginable – aviation, retail, banking and finance, agriculture, ports, insurance, transport, energy, and even chemical production.

What many people do not realise is that government involvement in business is not just inefficient. It is at the heart of our debt and economic crisis. SOEs are heavily indebted, crowd out credit that should go to the private sector, and operate in areas where private businesses could be far more productive.

Once upon a time, there was an argument that the government should be in business to ensure a ‘level playing field.’ That argument has long expired. Today, SOEs do not level the field, they tilt it. With mounting losses, inefficiency, and distortions, they have undermined competitiveness rather than protected it.

The State already has a stake

It is worth remembering that the Government already has a built-in stake in every business through taxation. Corporate tax is 30% of profits, and once businesses cross the Value-Added Tax (VAT) threshold, a further 18% is levied on value addition. In other words, the State captures a significant share of private profits without having to own or operate businesses.

The problem is that Sri Lanka has too few private businesses because the State has occupied their space and run it unproductively.

The real giants of losses

Closing 33 SOEs is good, but it is only the beginning. Sri Lanka has more than 500 SOEs if one includes subsidiaries and sub-subsidiaries. Some even operate as departments – railways and postal services, for instance, which are technically not SOEs but still run as commercial operations.

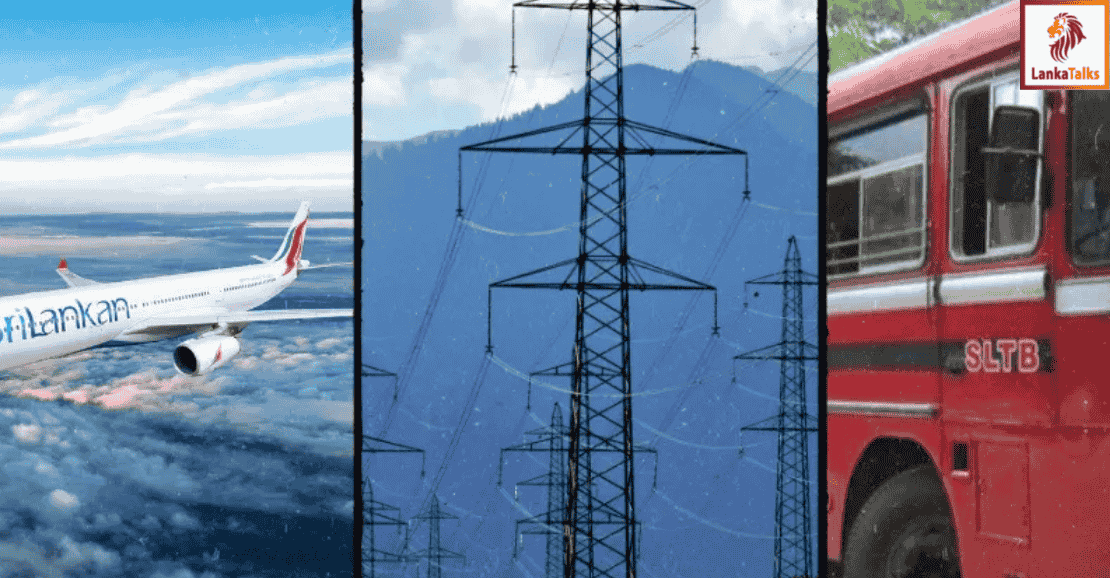

In reality, around five large SOEs account for 80% of the losses. These are:

- Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB)

- Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC)

- National Water Supply and Drainage Board (NWSDB)

- Sri Lanka Transport Board (SLTB)

- SriLankan Airlines

Restructuring these giants is critical. Attempts have already been made with the CEB, but as this column has previously argued, reform has been slow and the hurdles to attracting capital remain high.

SriLankan Airlines is another pressing case. Our sovereign credit rating remains partly hostage to the airline’s bond restructuring. The CPC and SLTB are not far behind in the severity of their problems.

A web of loss-making interconnections

One reason Sri Lanka went bankrupt was the unhealthy web of financial interconnections between these SOEs. When the CEB sold electricity below production cost, it borrowed fuel from the CPC, making the CPC loss-making as well.

The CPC, in turn, tried to recover losses by charging SriLankan Airlines higher-than-market prices for jet fuel. The airline was compelled to buy from the CPC since both were Government-owned and it too bled losses.

When all three made losses, they turned to the People’s Bank and Bank of Ceylon for loans, exposing depositors’ money to undue risk. With large amounts of credit guaranteed by the Treasury, private businesses were crowded out both by lack of funds and unfair competition.

A tilted playing field

The distortion is not confined to energy and transport. In insurance, for example, the law required all companies to split life and general insurance operations. The only exception? Sri Lanka Insurance – the State player.

In gaming, the new regulatory authority does not cover the National Lotteries Board or the Development Lotteries Board and private players are barred from entering the lottery market.

In ports, the problem is even more blatant. The Sri Lanka Ports Authority is both regulator and operator. It owns shares in private terminals such as Colombo International Container Terminal (CICT) and South Asia Gateway Terminal (SAGT) while running its own Jaya Container Terminal. It is regulator, competitor, and shareholder all rolled into one. That makes the very idea of a level playing field a joke.

Mixed signals

While shutting down 33 institutions, there are also news reports of the Government expanding into new businesses, such as opening outlets for sugar sales. These mixed signals send the wrong message.

The principle must be simple: the Government should focus on its core mandate – ensuring the rule of law – and let the private sector drive commercial activity. If necessary, regulate. But only when necessary. The State should take its 30% tax share, make tax administration efficient, and leave the rest to entrepreneurs.

The way forward

The next step is the passage of the proposed SOE holding company bill. This will bring most SOEs under a single holding company structure, paving the way for divestiture, Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs), and, where appropriate, outright privatisation.

Some SOEs must be privatised fully. Others should enter PPPs. But the guiding principle should remain the same: let the private sector run businesses, not the State.

Closing 33 SOEs is a start. But unless we confront the inefficiency of the big five and end the distortions that SOEs create across the economy, Sri Lanka will remain stuck in the same cycle of loss, debt, and stagnation.

Natasha

Natasha