Cyclone Ditwah exposed critical gaps in Sri Lanka’s health and disaster response systems.

Health and disaster agencies lack integrated dashboards and real-time data, forcing frontline workers to rely on informal, siloed information during emergencies.

Building integrated coordination platforms and climate-health surveillance systems can create climate-resilient health systems.

As Sri Lanka currently counts human and economic costs of Cyclone Ditwah, the images are both disturbing and somewhat familiar: flooded hospitals, access roads buried by landslides, evacuation centres overflowing with displaced families, and officials in health and disaster management services scrambling to meet everyone’s needs. The death toll is at 355 and rising, with hundreds more missing and over 200,000 displaced, with effects being borne disproportionately in the central hills and low-lying river basins across the country. It has once again placed the spotlight on the preparedness of our disaster response ecosystem, and with climate-related disasters no longer a few and far between, Cyclone Ditwah is a tragic but predictable reminder and caution of the same vulnerabilities that have persisted for years.

A recent chapter of the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka’s (IPS) State of the Economy report examines how climate risks intersect with Sri Lanka’s health infrastructure, disease profiles, and governance. In the aftermath of Ditwah, there must be an urgent call to reassess Sri Lanka’s disaster preparedness.

Cyclone Ditwah and Vulnerabilities in Health and Communities

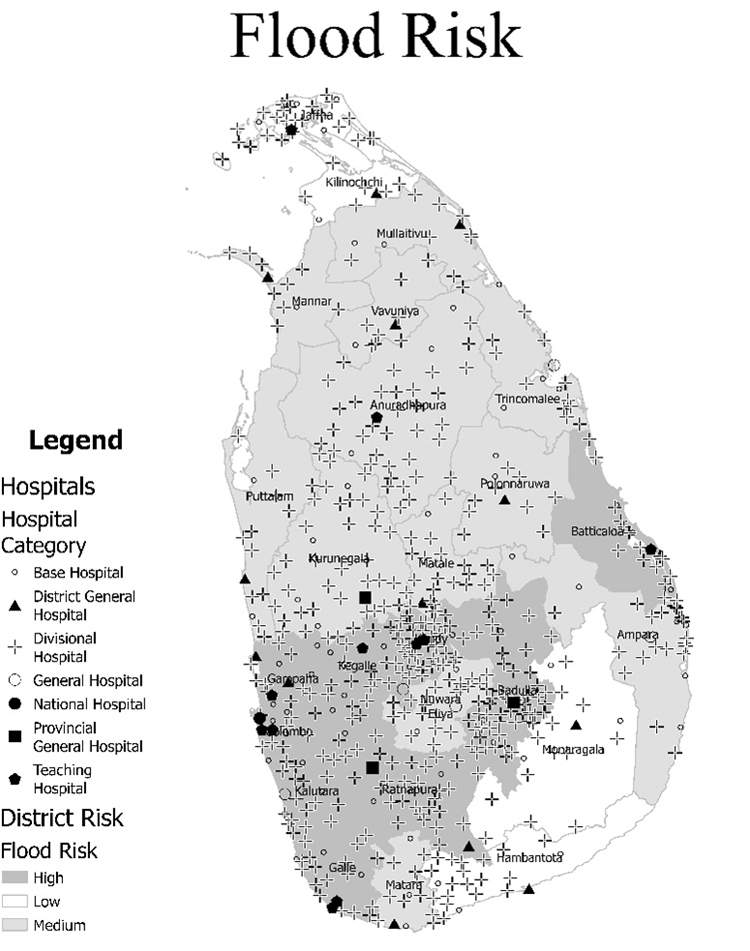

A considerable number of hospitals and divisional medical centres of Sri Lanka operate in flood-prone and landslide-risk areas throughout the country. Figure 1 shows that the analysis of health facilities against national hazard information reveals the location of hospitals by type that exist in districts that currently face the most severe Ditwah impacts in the central highlands and Sabaragamuwa, Gampaha, and Colombo’s surrounding low-lying urban areas. When rivers overflow, health facilities themselves become vulnerable, not just lifelines.

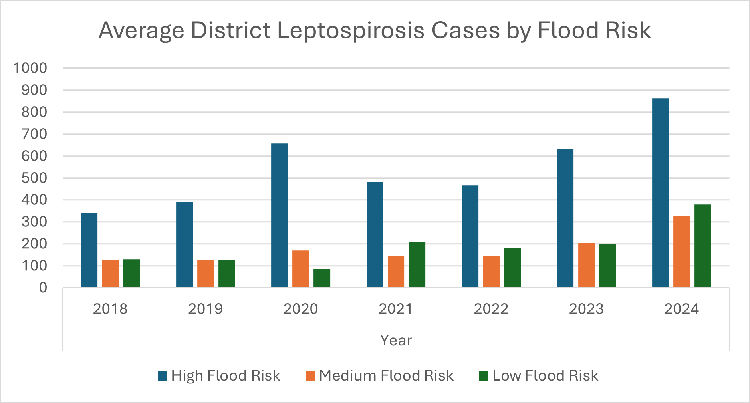

Moreover, the physical exposure quickly becomes an epidemiological risk. Flood-prone districts tend to report some of the highest average annual numbers of dengue and leptospirosis cases. While access to routine care and emergency transport is disrupted, heavy rainfall and poor drainage create ideal conditions for the spread of vector- and waterborne diseases. Ditwah will therefore not only create an immediate trauma burden, but likely a second wave of climate-sensitive illnesses among people in the most exposed communities.

Climate projections suggest more intense and frequent extreme weather, with a large share of Sri Lanka’s population expected to live in climate “hotspots” by mid-century. However, the transformation of the health system to address the climate reality is occurring at a slower pace than the rate at which climate change is affecting Sri Lanka.

Figure 1: Hospital Exposure to Flood Risk

Note: Hospital data sourced separately from the National Spatial Data Infrastructure (NSDI).

Source: Based on Zubair, L., et al. (2006). Natural Disaster Risks in Sri Lanka: Mapping Hazards and Risk Hotspots, Chapter 4. Natural Disaster Hotspots Case Studies. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Figure 2: Average District Leptospirosis Cases by Flood Risk

Source: Zubair, L., et al. (2006) and Weekly Epidemiology Reports, MOH

Data and Coordination Lag Behind Frontline Needs

Sri Lanka has strong technical capacity in many parts of its health system and a national Disaster Management Centre (DMC) with a mandate for early warning and response. Yet the overall architecture of disaster and climate risk governance remains fragmented, with the Ministry of Health and the DMC, particularly at the local level, and other agencies linked more by ad hoc coordination. This severely undermines the preparation of relevant stakeholders, even in highly predictable natural disasters such as Ditwah.

In the IPS State of the Economy findings on the topic, health officials and frontline workers report how, even in “normal” times, they juggle multiple unconnected reporting formats and databases. During a large-scale disaster like Ditwah, district health authorities would benefit from real-time information on displaced individuals and households, facilities and their occupancy, and the availability of medicine and staff. Currently, much of this is still pieced together informally or in silos rather than through integrated dashboards that bring hazard, health, and facilities data together.

Additionally, the health-disaster ecosystem loses its ability to monitor diseases as dengue, leptospirosis, and diarrheal diseases, which need to be tracked during heavy rainfall and after floodwaters recede. The current system fails to connect meteorological data with health information systems and prevents the conversion of weather alerts into specific health warnings for local areas. Ditwah is therefore exposing not only weaknesses in physical infrastructure, but also the absence of a joined-up “climate and health” information system.

Digital Fortification: What We Must Build Before the Next Ditwah

One of the core ideas in the IPS report chapter is the need for “digital fortification” of the health sector. A quick and effective solution is an integrated emergency coordination platform that connects the DMC, Ministry of Health, provincial and district health offices, hospitals, and field staff. It can provide a shared picture of affected populations, and regularly update the status of health facilities, bed and drug availability, ambulance routes, and staff deployment. Additionally, a climate and health surveillance system that combines real-time climate and hazard data with routine disease reporting can flag high-risk areas for dengue, leptospirosis, and other climate-sensitive conditions.

Both interventions can be built on existing digital health tools, such as the Hospital Health Information Management System. It would require expanding coverage, backup power for connectivity, and the personnel and training necessary to raise efficiency. Linking these tools to geographic information systems would allow planners to see which facilities are at risk of being cut off and how best to coordinate vertically within health and disaster management systems, and horizontally across them.

From Tragedy to Transformation

Digital solutions do not substitute investments in infrastructure, staff, or primary care. However, they present feasible ways forward in a recovering economy to stretch limited resources by providing decision-makers with timely, detailed information and tools. As climate disasters become more frequent, Sri Lanka cannot afford not to invest in simple yet effective solutions.

Cyclone Ditwah is a national tragedy. It should also be a turning point in how we think about climate resilience in the health sector. As reconstruction support and international assistance are mobilised, Sri Lanka has an opportunity to ensure that “building back” includes building more intelligent, more connected, and more anticipatory disaster preparedness systems.

adaderana.lk

A.R.B.J Rajapaksha

A.R.B.J Rajapaksha